ISTVÁN LÁSZLÓ G. SHORT BIO AND TEXTS

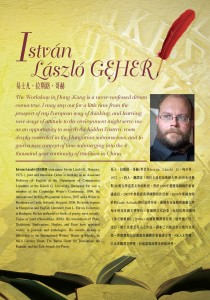

István László GEHER (pen name: István László G., Hungary, 1972- ), poet and translator. Geher is working as an Associate Professor of English at the Department of Comparative Literature at the Károli G. University, Budapest. He holds degrees in Hungarian and English Literature from L. Eötvös University in Budapest. He was a member of the Cambridge Writer’s Conference, 1999, the International Writing Programme in Iowa, 2007

István László GEHER (pen name: István László G., Hungary, 1972- ), poet and translator. Geher is working as an Associate Professor of English at the Department of Comparative Literature at the Károli G. University, Budapest. He holds degrees in Hungarian and English Literature from L. Eötvös University in Budapest. He was a member of the Cambridge Writer’s Conference, 1999, the International Writing Programme in Iowa, 2007

International Writers in 2007

Poems in Words Without Borders, November, 2007 : Jungle, Chrystal study

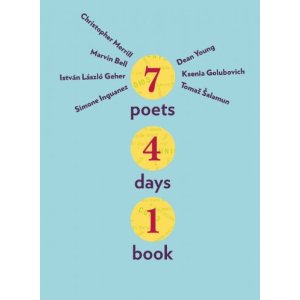

He also co-authored in Seven Poets, Four Days, One Book, 2009, collaborative poems, written during the Iowa International Writing Programme. The Book was edited by Christopher Merrill, head of the IWP.

He also co-authored in Seven Poets, Four Days, One Book, 2009, collaborative poems, written during the Iowa International Writing Programme. The Book was edited by Christopher Merrill, head of the IWP.

order 7 poets, 4 days, 1 book here

read review of 7 poems, 4 days, 1 book

Video of the book launch in October 9, 2009 part 1 part 2 part 3 part 4 part5 part6

In 2008 he was an invited member of the Internaional Writers Workshop in Hong Kong.

about the programme

the writers

Schedule of the Festival

picture

From 2002-2004 he was leader of the British Council’s poetry translation seminars with poet friends. In 2004 October he participates in a reading tour called Converging Lines, in England. In Spring 2008 he was invited to Athens to the Iowa in Athens Poetry Festival.

about Converging Lines UK diary Oct 04.qxd

about the event in Athens

about the event in Athens

in Greek

István László G. Poems in Greek

In 2010 his poems appeared in Η κοινή μας φούγκα Ανθολογία νέων Ούγγρων ποιητών, an anthology of Young Hungarian Poets in Greek. The Title „Fuge in Common” is coming from one of his poems.

here you can buy the Anthology in Greek

In Autumn 2008 he gained a three months‘ scholarship in Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart as a fellow writer. His selected poems Sandfuge were published in a German-Hungarian bilingual edition last autumn. He has authored six books of poetry, most recently Fugue of Sand (Homokfúga, 2008). His book of poetry translations Pentagram came out in 2009.

In Autumn 2008 he gained a three months‘ scholarship in Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart as a fellow writer. His selected poems Sandfuge were published in a German-Hungarian bilingual edition last autumn. He has authored six books of poetry, most recently Fugue of Sand (Homokfúga, 2008). His book of poetry translations Pentagram came out in 2009.

Here you can order Sandfuge (Sand of Fuge, Selected Poems in German, Bilingual Edition) / bestellen

In 2010 his poems appeared in the Anthology of Post 1989 writers edited by George Szirtes.

here you can buy NEW ORDER, Hungarian Poets of the Post 1989 Generation / bestellen

He defended his PhD in 2010, the doctoral dissertation titled Deconstructed Rhythm came out in 2014.

In 2013 he was a guest at Levoce Festival in Slovakia. and Novi Sad Festival in Újvidék. In 2015 his poems appeared in Serbian in the 10. Novi Sad International Literary Festival Anthology.

Main prizes:

1999 Zsigmond Móricz Scholarship,

2006,2011, 2014. The National Cultural Found’s Creative Scholarship,

2006″Pebble from Nizza” Prize,

2006 Miklós Radnóti Prize for Poetry

2007 Mihály Babits Translator’s Scholarship

2007 Zoltán Zelk Poetry Award

2011 Attila József Prize

2012 Milán Füst Prize for Poetry

Books:

1994 Öt ajtón (Through Five Doors, poems)

1996 Kereszthuzat (Cross Draught, poems)

1998 Merülő szonettek (Submerging Sonnets)

2001 Napfoltok (Sunspots, poems)

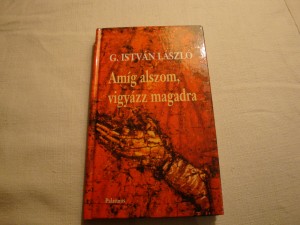

2006 Amíg alszom, vigyázz magadra (Take Care of Yourself While I Sleep, poems)

2008 Homokfúga (Sand of Fuge, poems)

2009 7 Poets,4 Days, 1 Book, Colleborative Poems in the Iowa International Workshop

2009 Sandfuge (Sand of Fuge, Selected Poems in German, Bilingual Edition)

2009 Pentagram (Pentagram, Poems Translated from English)

2011 Aqua fortis (Választóvíz, poems)

2013 Tryptichs (Hármasoltárok, poems)

2014 Deconstructed Rhythm (Dekonstruált ritmika, doctoral dissertation)

2015 Flying Carpet (Repülő szőnyeg, poems)

2017 I haven’t Committed It (Nem követtem el, poems)

2019 Groundcloth (Földabrosz, poems)

1994 Through Five Doors (Liget)

One of the most talented poets of his generation, István László G. found his unique poetic voice as early as in his first volume. The theme of his poems would be difficult to grasp, as he creates an inner landscape through surrealistic, bizarre images from everyday experiences and woodland scenes. In this volume, short, closed forms prevail. Out of the five cycles (the “five doors”), it is „Csomók, balladák” (“Knots and Ballads”) and „Hangok között” (“Among Voices”) that stand out especially, in the former one there are paraphrases from world literature (Eliot, Yeats) and ballads with dense texture and private content, in the latter one, texts sometimes given to personas from world literature, and though the dramatic situation remains hidden, yet, owing to their intensity, they become suggestive and elevated.

One of the most talented poets of his generation, István László G. found his unique poetic voice as early as in his first volume. The theme of his poems would be difficult to grasp, as he creates an inner landscape through surrealistic, bizarre images from everyday experiences and woodland scenes. In this volume, short, closed forms prevail. Out of the five cycles (the “five doors”), it is „Csomók, balladák” (“Knots and Ballads”) and „Hangok között” (“Among Voices”) that stand out especially, in the former one there are paraphrases from world literature (Eliot, Yeats) and ballads with dense texture and private content, in the latter one, texts sometimes given to personas from world literature, and though the dramatic situation remains hidden, yet, owing to their intensity, they become suggestive and elevated.

1996 Cross Draught (Liget)

The inward eye ultimately gives way to dreams in the second volume. The breath of the poems are longer, and the first cycle called “Sound and Shadow: Dream Poems” can be considered one long poem. Ilona Legeza writes of this cycle, “these are dream poems; childhood dreams or adult dreams going back to childhood, dreamlike reveries or recollections of old scenes in the dream. These dream-landscapes are incidentally rather prosaic, a hall, a kitchen, a stairway, an evening bathe, a short trip, a swim near the bank – “only by the bank, it’s allowed there only” –, a slight illness, a dinner etc. What is dreamlike in them is the poems’ atmosphere, their strange iridescent state, the dimness of all outlines, or, their unreal definiteness, a general prevailing of the synecdoche, the pre-logical or magic way of thinking characteristic of children, the constant, almost compulsive, recurring of certain lines, expressions and syntactic units.”

The inward eye ultimately gives way to dreams in the second volume. The breath of the poems are longer, and the first cycle called “Sound and Shadow: Dream Poems” can be considered one long poem. Ilona Legeza writes of this cycle, “these are dream poems; childhood dreams or adult dreams going back to childhood, dreamlike reveries or recollections of old scenes in the dream. These dream-landscapes are incidentally rather prosaic, a hall, a kitchen, a stairway, an evening bathe, a short trip, a swim near the bank – “only by the bank, it’s allowed there only” –, a slight illness, a dinner etc. What is dreamlike in them is the poems’ atmosphere, their strange iridescent state, the dimness of all outlines, or, their unreal definiteness, a general prevailing of the synecdoche, the pre-logical or magic way of thinking characteristic of children, the constant, almost compulsive, recurring of certain lines, expressions and syntactic units.”

Dreams, dream-evidences retain an important role in the later poems of the book, whether stated in one single song that is linguistically simple, although surreal in its images and logics („Harangozásra” / “For the tolling of the bell”; „Évszakok születése” / “The Birth of Seasons”, „Körtánc”/ “Round Dance”), or having some dream-story („A kastélyban”/”In the Castle”; and all the poems of the last cycle). It is in connection with the concept of the dream that in this volume, the images of vision and blindness gain a symbolic role. In the last cycle, like in the first one, the loneliness that dreams its dreams elsewhere appears in the vicinity of others and in collective places (a canteen, at a party, on a bus, in the pool).

1998 Submerging Sonnets (Belvárosi Kiadó)

The third volume, one of István László G.’s most strictly organized and most unified books, comprises twice fifteen sonnets. The undertone of the poems is passion, their unnamed experience is perhaps closest to angst, desire or thirst (whose object can be God, some completeness or another person, but at times the speaker addresses himself in them). The seemingly arguing structure of the sentences follows some autonomous logics and this way, and through their strong musicality, they pull the reader through themselves. They state one or two fragments of experiences, this is how much there is to grasp, yet each poem works as a whole, and by sheer logics they are almost impossible to untangle, so ultimately it is the inexpressible experience that talks in them.

The third volume, one of István László G.’s most strictly organized and most unified books, comprises twice fifteen sonnets. The undertone of the poems is passion, their unnamed experience is perhaps closest to angst, desire or thirst (whose object can be God, some completeness or another person, but at times the speaker addresses himself in them). The seemingly arguing structure of the sentences follows some autonomous logics and this way, and through their strong musicality, they pull the reader through themselves. They state one or two fragments of experiences, this is how much there is to grasp, yet each poem works as a whole, and by sheer logics they are almost impossible to untangle, so ultimately it is the inexpressible experience that talks in them.

„… reading his third book makes me glad. There are mature poems aligning in front of me, all excellent in their own unique way, and the author has his own, unified voice that differentiates him from his fellow poets. His severity has not fallen prey to any temptation. He had the nerve not to stop at the attractive half-ways of shaping a poem, where he obviously had everything in the lines he wished to put into the poem, yet his high expectations forced him to go on and find the ultimate expression. And here is the result, he steps in front of us with a spotlessly finished lyricism, he carries his modern-unique contents without compromise, and in a way that this enormous inner work does not transpire in the poems, whose surface is so perfect and beautiful and, seemingly, simple as if nothing would be more natural than what he is saying. The weights emerge when one reads them for the umpteenth time, and these two together, beauty and weight, offer us a magnificent and deep poetry.” (Magda Székely)

2001 Sunspots (Liget)

Three times thirty three poems and a poetry translation (from Emily Dickinson). Yet the poems themselves are open (and indication of this may be that they usually have no title), they are loosely connected, and their images are more mosaic-like. There are poems with a denser texture and unexpected, shockingly strong lines (“What kind of guarding”; (In the Cloud); “There’s River-current in the Stone”), songlike quatrains, and a longer cycle: “(The Danube Manages)”, in which figures of contemporary Hungarian society speak their last soliloquies (similarly to János Arany’s poem, “Hídavatás” / “Bridge-opening”).

Three times thirty three poems and a poetry translation (from Emily Dickinson). Yet the poems themselves are open (and indication of this may be that they usually have no title), they are loosely connected, and their images are more mosaic-like. There are poems with a denser texture and unexpected, shockingly strong lines (“What kind of guarding”; (In the Cloud); “There’s River-current in the Stone”), songlike quatrains, and a longer cycle: “(The Danube Manages)”, in which figures of contemporary Hungarian society speak their last soliloquies (similarly to János Arany’s poem, “Hídavatás” / “Bridge-opening”).

„ István László G.’s poems are volatile, elusive: they do not have a story, some content that could be recalled, there are only the images drifting and running into one another in them. As if blocks of words with different substance and weight would stand together: in a way that what we read is not only the assembly of words, but some musical, mathematical unit in which the meaning of the words is only one of the weighing elements, but the structure is organized according to some deeper, unconscious logics. We get into the whirl of a subjectless and endless monologue. There are impressions and sensations swirling: it is never once stated what indeed the poems coil around. As if writing itself was a slow, concentric approach to its own ungraspable subject. Staring and dizziness are recurring motifs, and meanwhile the poems mime the same whirling with their own devices, they turn around, return to their beginning, circumscribe the unspeakable, modelling with their very structure the course of thinking itself /…/ This is the landscape of inner perspectives with its trees, stones and river mouths: the personality widens inwardly and dissolves into the impersonal in a world that is reconstructed from fragments of vision. /…/ The sadness of sustained attention reverberates in István László G.’s sentences: “Your dress smelling of herbs – / it surrounds you with clouds that you are not / fit to be human.” It is not some kind of tearful sorrow, on the contrary; it is wide, attentive, leisurely, thrillingly strange and eternal, just like an angel’s eye staring at a sunspot.” (Krisztina Tóth)

2006 Take Care of Yourself While I Sleep (Palatinus)

The fifth and yet again strongly organized book comprises two larger parts, each divided into three cycles. They are divine poems in the sense that at the same time they are closely connected to the emotional areas covered earlier (loneliness, absences, thirst, seeking).

The fifth and yet again strongly organized book comprises two larger parts, each divided into three cycles. They are divine poems in the sense that at the same time they are closely connected to the emotional areas covered earlier (loneliness, absences, thirst, seeking).

„In his new book, following one of the centuries-old traditions of Hungarian poetry, István László G. expresses a deeply felt inner struggle of doubt and belief. In the first half of this book composed by mathematical punctuality and musical inventiveness he builds a cathedral from poems, moreover, as some Gothic church-building master, he decorates the facade with stonework, so that from now on, in the second half, prayers, psalms, supplication and dialogue shall be uttered in this space built from words. In the dialogue with God he first confesses his doubts from which he creates his own Creator, only to be able later to present God’s inner drama, his own self-destructing doubts – the paradoxical proof of his existence. The addressing of God unfolds from the drama of self-addressing, and the other way round, the emphasis of prayer is gradually transferred from the praying person to the listener of the prayer: ‘I close my eyes’ – ‘close your eyes on me’. István László G.’s polyphonic poetry is the summary of the self-examination of a restless and scrutinizing mind. His voice fills this self-created space with shocking clarity.” Győző Ferencz

Dénes Krusovszky writes: „/The first part called “Cathedral”/ … implies in its title the manifold space where the speaker of the poem seeks God (who can be considered here the synonym of the Other, of the unknown): Cathedral, Burger King, Railway Restaurant. The main question is to be found in the very first line of the book: ’What is the headstone of fear?’ (‘Cathedral’). This refers to the fear of God, and consequently, to the fear of God’s non-existence, a metaphysical loneliness. The second smaller section tries to answer the questions of the first one by examining everyday faces and situations, trying to infer from them the non-everyday. /…/ The third section pushes off from this point and, quite unexpectedly, jumps back to myths. Through a couple of figures from Sumerian, Greek-Roman and Jewis-Christian culture, it seeks in an obsessed way what he sought earlier in the Burger King. Naturally, there are no ultimate answers to final questions here, yet the task is important: ’Like a piece of broken earthenware, to put together / its fragments is not useless for nothing’ (‘Istar’s balance’). This is one of the most exciting parts of the book, especially since what we read here lead to the more personal lyricism of the second great part. The sequence of the texts in the part called ‘Take Care While I Sleep’, whether dialogic, confessional, self-addressing, God-denying or swearing, symbolically opens with the poem ’Faithless’: ‘Lord, don’t play with meg, don’t save me with the fire’ and ends with ‘Close Your Eyes On Me’: ‘I’ll say a first prayer / for you, take it as if it was / conceived in you, as on your mirror: you shall close your eyes on me’. And all this while it travels on a road that everyone seeking to find their place in this world is bound to travel on, without the chance of the least possible resignation, and in the end he can only ask God (whatever it is): ‘And who are you praying to?’ (‘Close Your Eyes On Me’).”

2008 Fuge of Sand (Palatinus)

POEMS

BURGER KING

As if their heads were so many conkers,

brown light-cracks muscling through their cells of pins,

the men are eating.

They are not thinking of women or of heaven,

but banging open greased-up wrappers

with mayo weeping through white napkins;

they bite off more than they can chew

while food-gauze comes like Velcro from its wounds.

With mouthfuls barging round their mouths

and pushing in along the tounge

as if by being swallowed they’d be born,

they are eating, all alone.

(trans. by Anthony Dunn)

BURGER KING

As if their heads were conkers,

brown cracks of light pressing through split cases,

the men eat.

They don’t think about women, the waiting years,

but unravel instead the grease – proof paper,

the mayo bleeding the white napkins,

and sink into the burgers,

pulling away like gauze from half-healed skin.

The food turns in their mouths,

gropes about the palate of bone

as if it might be born in this swallowing,

the men eat, alone.

(transl. by Owen Sheers)

THE FISHMONGER

This then, is the age of the fishmonger, not the fisherman –

his cap tipped as a sergeant’s, unsteady on his quiffed head

as he sizes up punters, measuring their movements.

He reaches for a carp as easily as you or I

might dip our hand into a bucket of apples,

feels for the fish, his ingrown nail smarting in the salty water,

and lifts it out, understanding as only he can,

the foil disc of the silver eye, the wight of the blade,

the engine-stroke of his heart, finely tuned to this cruel kindness.

Understanding as only he can, the spot between the knuckles

where a nail might enter as if through butter,

how to slice flash as others cut celery,

how to pare his speech as he might men

were he hurt and pushed to fight.

But like a tree hit by lightening, there is no healing bark

about his struck heart and the wood and the trunk’s centre

pulses and grasps for growth like a fish

struggling for its last breath as if biting the air for water.

(Owen Sheers’ Adaptation)

FISHMONGER

This is his day. On the crest of his hair,

like some military mock-up,

his cap lists; he weighs up the punters

by their quickest flickers, pulls out carp quick snap,

keeps his in-growing fingernail stinging

in fish water –

got to feel

the heads of the fish. The silvering eyes

only make sense to the man

with gut-knife in hand, in his gut his intent

to the cut; the man who does what he does

for us all, who does what he must, what is meant;

who knows the points at ankle, wrist,

to best hammer a nail in; who can fillet

a man easy as you’d ease open

one of these fish, who cuts the chat

to let his blade do the talking; tidy; fights when he hurts.

There is no bark around his heart. I mean picture a tree

nailed by lightning, the hanging flash of it aflame.

No I meant

the fish aflame in his hands, its last supper, its mouthing

for water in the air.

(transl. by Antony Dunn)

HEADWAITER

Not his strength; he employs his accurate

gaze, his deodorant-tone; a sleepy

musician disregarding his beat,

he moves things around – waste paper, stained table-cloths,

drips of wax varnishing his nails, a blindly

accomplished ritual among the paraphernalia

of the acolyte’s long service.

table five wants the bill.

There is no elevation of the host, but the palming of the tip,

starched thanks.

Flat footed. Casual attention. reserved,

measured rests.

In his head, the faces of his guests are a graveyard.

A ritual without kaddish, as if he’s digging,

he brings in round upon round, the orders for afters.

So many stomachs for the earth to swallow down,

to inter, invisibly. A new company.

Elegiac pose, sweet laughter, the gourmet’s salad of leaves.

Salt is spilled. A plate slips, falls.

Every one is family, every one bereaved.

Every one is happily deceased.

(transl. by Antony Dunn)